The architecture of reunification at Potsdamer Platz and Kulturforum

An architectural tour through Potsdamer Platz and the Kulturforum, regions which represent the reunification and rebirth of the city.

The second part of the Berlin Contemporary Architecture Guide focuses on two iconic neighboring areas of the city: Potsdamer Platz and the Kulturforum. Both parts of the former Tiergartenviertel, their history of development, destruction, ostracism, and rebirth are similar in many aspects to what happened in most of Berlin. The scale of it, however, is unprecedented. Potsdamer Platz and the Kulturforum represent the endurance of Berlin and are a test of the power of architecture and urban planning to rebuild and reunite a divided country. The suggested route in this section proposes an exploration of Potsdamer Platz and its surroundings, with buildings by Renzo Piano, Helmut Jahn, Hans Kollhoff, Richard Rogers, Rafael Moneo, and many others. Further west, the Kulturforum opens up and offers fantastic classics such as Hans Scharoun's Philharmonie and Mies van der Rohe's Neue Nationalgalerie.

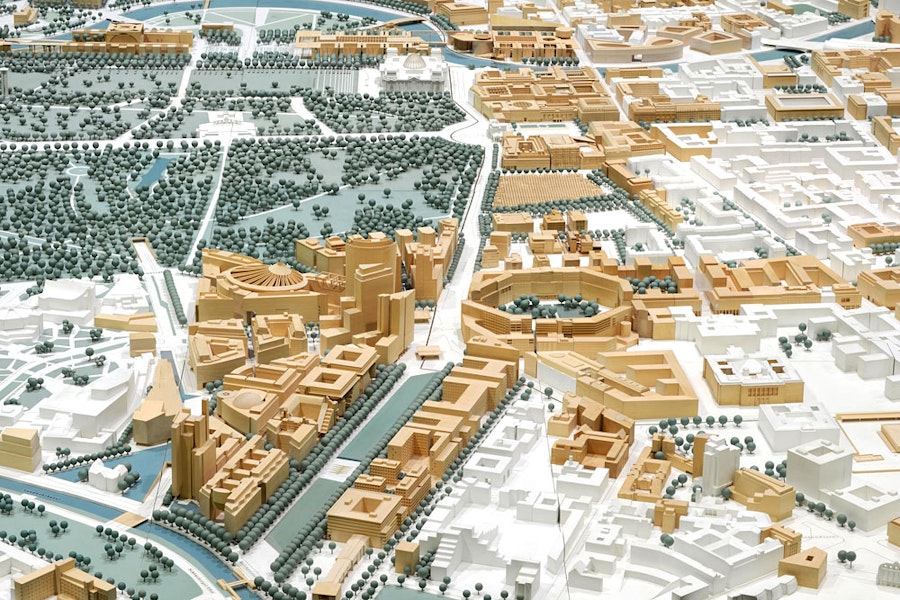

Map

Black icons are mentioned in the articles, while gray ones are further recommendations (direct link):

Buildings

- Postdamer Platz

- Potsdamer Platz 11 - Renzo Piano Building Workshop

- Daimler-Chrysler - Richard Rogers

- Debis Tower (Eichhornstrasse 3) - Renzo Piano Building Workshop

- Kollhoff Tower - Hans Kollhoff

- Sony Center - Murphy/Jahn

- Kulturforum

- Philharmonie - Hans Scharoun

- Neue Nationalgalerie - Mies Van der Rohe

- Berlin State Library - Hans Scharoun

Postdamer Platz

The Potsdamer Platz carries a unique history. It was one of the earliest entrance gates to the city, where commerce and people gathered outside Berlin’s old customs wall. It was never a square per-se but a five-cornered road intersection. Located outside the city walls, it was not subject to guidelines and constraints from general urban planning. Its development was organic and uncontrolled. In contrast, its neighboring Leipziger Platz, located inside the city walls, was from its beginning designed as an octagonal square with all the rigor and form expected for an important square in the capital of the Prussian Empire.

Throughout the year, city planners tried to unify and give an order to both squares. But nothing ever came to reality. With the city’s expansion, Potsdamer Platz’s size and importance exploded. The dismantling of the old city walls in 1866 and the arrival of the railways in the following years culminated in turning the Potsdamer Platz into one of the greatest hubs in Europe, akin to Piccadilly Circus in London or the Times Square in New York. It was the busiest traffic center in Europe. It redefined the center of Berlin and acquired legendary status worldwide. It all came to an end during the Second World War. Air raids turned the whole area to rubble. During the Cold War and the Berlin Wall, Potsdamer Platz was nothing but a vast expanse of empty land. It was a no-mans land between East and West Berlin. It became a symbol of the divided nation.

With the fall of the Berlin wall in 1989, the city started planning the unification of Germany in the form of several large-scale urban interventions. One of the largest and most significant new areas was the Potsdamer Platz and the adjacent Tiergartenviertel. Located at the dividing line between East and West Berlin, the 60 ha area right in the center of the capital became the most exciting building site in the world.

The general planning followed the winning proposal from Munich-based architects Hilmer-Sattler. It divided the area into for large parts. Separate investor acquired each area for further development:

Daimler-Benz

Daimler-Benz (later Daimler-Chrysler and now Daimler AG) received the largest part. The Italian architect Renzo Piano was put in charge of its plan. In collaboration with architects such as Richard Rogers and Hans Kolhoff, he built the whole area between 1993 and 1998.

Sony Center

Sony received the second largest among the four parts. Architect Helmut Jahn designed the iconic Sony Center and the shiny glass tower for the Deutsche Bahn.

Beisheim Center

The German businessman Otto Beisheim financed from his own pocket the third part. Composed of hotels, offices, and residences, the group of buildings contain works from David Chipperfield, Hilmer Sattler, Hans Kollhoff, among others.

Park Kollonnaden

The last of the four parts (Park Kollonnaden), located in the southernmost part of the whole development was planned by Italian architect Giorgio Grassi. It contains a series of buildings facing the Tilla-Durieux-Park, housing offices and residences designed by several architects such as Diener & Diener, Schweger & Partner, among others.

Tour

The area is now developed and already plays a significant role in Berlin. Most locals see it as a tourist trap, where food is expensive, the primary goal is shopping, and where only rich people live. It has indeed a character not found anywhere else in Berlin. Instead of the organic, vivid, and sometimes messy feel of Berlin’s eastern neighborhood, you’ll find an ordered, clean and aseptic environment.

While living in Berlin, I would only intentionally go to Potsdamer Platz for two reasons. The number one was to catch a movie in one of the few non-dubbed cinemas in town in the Sony Center (the Germans’ appreciation for dubbed movies drives me nuts). The second reason was to bring visitors to check it out. It is a fantastic place to witness how Berlin brought itself back from such a convoluted past.

The walk I usually do to check the coolest buildings start at the Daimler Benz section, checking out buildings from Piano, Rogers, Kollhoff, and others. We then jump to the Sony Center, one of the main attractions. But there is much more to explore. Spend some time walking around the area, checking out other buildings from Rafael Moneo, Arata Isozaki, Chipperfield, and others. The Film Museum in the Sony Center is excellent, and the Legoland is super fun with kids. Also, the IMAX is always a good place to be in on a rainy Berlin day.

Potsdamer Platz 11 - Renzo Piano Building Workshop

The leftmost tower from the trio on Potsdamer Platz is Renzo Piano's Potsdamer Platz 11. This tower takes the triangular plot to its extreme. Its sharp edge reads as an arrow, or a compass needle, pointing to the center of the square. It carries Piano's signature style, with double glazed facades with a delicate steel structure, much like his New York Times Building, in New York, or The Shard, in London. Towards the back, terracotta tiles cover the facade, an appearance which Piano repeats on most other buildings in the area. The massing falls to the level of all other buildings. It stands next to Haus Huth, one of the few historic buildings still standing in the area. It houses an excellent contemporary art collection from Daimler, who is also the principal investor in this section of the Potsdamer Platz.

Daimler-Chrysler - Richard Rogers

Following the street along the left side of Piano’s tower, you’ll find a series of three distinct buildings that stand out among all other buildings around it. British architect Richard Rogers designed it on commission from Daimler Chrysler. It contains offices in the first two blocks and residential in the last block. Retail functions occupy on the ground and lower floors. Renzo Piano’s master plan for the area called for typical Berlin blocks courtyard buildings with a maximum height of 9 stories. Rogers reinterpreted the constraints and designed courtyard buildings with an eroded corner. This would open up the courtyard, allowing sunlight to reach in and air to circulate through. The courtyard is then covered with a transparent membrane to provide climatic control.

The office buildings look like big high-tech machines: a mixture of metal, glass, exposed pipes and installations. Unexpected shapes complete the picture: large cylinder blocks covered with bright yellow louvers, or the staircase casing. Much of it is reminiscent of Roger’s earlier works such as the Lloyd’s Building in London, or the Pompidou Center in Paris. The housing block also presents some of the high-tech feeling of the office blocks, as well as the eroded corner which allows sunlight to reach all apartments and its internal courtyard.

Seen from the gigantic seesaws of Tilla-Durieux Park, all three buildings form a cohesive block which fits so well in between Piano’s terracotta-cladded buildings.

Daimler Chrysler

- 1999

- Office, residential, retail

- 70,000sqm

Debis Tower (Eichhornstrasse 3) - Renzo Piano Building Workshop

The tallest building in of the whole master plan, Renzo Piano’s Debis Tower stands 106-meters tall on the southern end of the development. Its lighthouse-style green cube sits atop a ventilation shaft for the Spreebogen Tunnel below and is visible from everywhere in the city. The tower carries own Piano’s signature on the use of terracotta cladding and reduced glass surfaces. But the tower is not the most interesting part of the building. Its plinth houses a very impressive 7-story high atrium, with a glass ceiling and surrounded by offices. But due to terror threats since 9/11, it is no longer accessible to the public.

Debis Tower

- 1997

- Office

- 38,200sqm / 106m

Kollhoff Tower - Hans Kollhoff

The Kollhoff Tower is the center tower on Potsdamer Platz. Named after its designer, German architect Hans Kollhoff, it presents a classical building style using traditional materials, resembling an old New York building. Kollhoff is sometimes accused of creating outdated “retro-architecture.” But the architect has a great attention to detail. You can notice it in the lobby design, on the fine divisions of the stepping façade, and the finishing top with golden accents. The tower houses an observation deck at the top and an exhibition about the history and development of the Potsdamer Platz. From there, you can also gaze down on the Beisheim Center north of the Bahn Tower, also designed by Kollhoff.

Kollhoff Tower

- 1999

- Office

- 31,700sqm / 101m

Sony Center - Murphy/Jahn

The Sony Center, designed by Helmut Jahn, is one of the coolest public spaces in Berlin. Its roof structure is iconic and came to symbolize the whole Potsdamer Platz itself. It is one of the few buildings in the area which offers a public plaza which is always lively and happening. The Sony Center, much like Roger’s building, is an interpretation of the planning constraints of the original master plan. Jahn took the central courtyard and transformed it in the main attraction, which he named the “Forum.” Around it, a mix of retail, offices, entertainment, and residential, with glazed facades and inclined facades, form its oval shape.

The roof above is the main attraction. Its oval shape is held by a large truss from which cables support the central mast and the Teflon and glass panels which form its surface. The structural principle is simple, like that of a bicycle wheel or a large Ferris-wheel. Its dimensions, location, lighting design, turn it into something extraordinary. Closer to the Bahntower you can find remains of the old Hotel Esplanade, formerly located on the site and destroyed during the war. The remaining lounge and breakfast room were moved over 75 meters from its original location. They are now used as a restaurant. Above it, suspended by yet another large truss (visible on the north façade of the compound), a group of apartments of different sizes overlooks the Forum.

The Bahntower is the third tower standing right on Potsdamer Platz, together with Piano’s tower and the Kollhoff Tower. It is tall and elegant but no rival to its next-door cupola and Forum.

Kulturforum

Right next to Potsdamer Platz you’ll find the region called Kulturforum (Cultural Forum). It is an area that gathers several important cultural institutions and architectural masterpieces such as Hans Scharoun’s Philharmonie and Mies van der Hohe’s Neue Nationalgalerie. The history of the Kulturforum area, or Tiergartenviertel, is closely tied to that of Potsdamer Platz. At the beginning of the 20th century, it was one of the noblest addresses in Berlin, with several high-profile citizens building villas and Summer properties in the area. During the Nazi time, the Tiergartenviertal was converted to a diplomatic district housing mainly embassies and consulates. The various air raids during the Second World War razed the neighborhood to the ground, giving place to new rebuilding plans to be carried out in the 1950s and 60s.

Following a plan from Hans Scharoun, the whole area was split into a diplomatic region to the west and a cultural region to the east. Originally a “spiritual ribbon of culture” would connect the Cultural Forum to the Museum Island. However, the appearance to the Berlin Wall made the West-located Cultural Forum not an extension, but a counterpart to the East-located Museum Island. The first building in the area was Hans Scharoun’s Philharmonie, followed by Mies’s Neue Nationalgalerie. Scharoun would eventually design other buildings to the ensemble, such as the Neue Staatsbibliothek and the Music Instruments Museum, completed after his death. The current ground of buildings received its last member with the completion of the Gemaldegalerie in 1998. Since then, modifications to the urban planning and new plans for the open areas in the Kulturforum attempted to complete the region as envisioned. However, it never quite achieved the status of a full ensemble, it feels unfinished and unbalanced. The solitary buildings are wonderful on their own, but there is still much to be done to give the Kulturforum its final form.

Philharmonie - Hans Scharoun

Created to house the Berlin Philharmonic and to replace the old Philharmonie building destroyed during the war, the Philharmonie is the key-piece of the Kulturforum. It is also Scharoun’s most important work. It is the embodiment of organic architecture principles, in which the buildings are designed from within. In this case, the built form reflects and establishes a balance with the music contained within. As Scharoun puts it, it is all about the music. The main hall presents a vineyard-style arrangement of the stage and audience, with terraces rising around a central orchestral platform. This feature led to the tent-like design of the hall’s ceiling, with a higher center draping down towards the edges; a move also reflected on the building’s outside appearance. The sequences of spaces leading to the hall play with tension and release. Low, small entrance areas lead to a vast, multi-layered foyer. Here, stairs in all directions, movements up and down, and a multiplicity of shapes play with the visitor’s senses. A smaller corridor leading to the hall damps the excitement and builds expectation which is then rewarded by the spectacular hall.

It is hard to imagine how such building was designed and built to such perfection. Fifty years ago, when computer simulations were still something in science fiction movies, Scharoun created an unusual and daring music hall with perfect acoustics. It set the standard to many music halls to come.

Neue Nationalgalerie - Mies Van der Rohe

Another key building in the Kulturforum is Mies’s Neue Nationalgalerie. It houses a museum of modern art in a simple but ingenious building. Above ground what you see is a large roof supported by eight columns. Below it, a glass box, more than eight meters high, houses large-scale temporary exhibitions. It is a free, open space, interrupted only by two large marble blocks and the stairways leading to the basement level. Downstairs, another large room houses the permanent collection overlooking a sculpture garden. It is straightforward and beautiful. There are no visual barriers between interior and exterior, between people and the art inside. Only the roof and a few columns define the space. Outside on the terrace, sculptures from Chillida, Serra, Gudari, and others, also era the boundaries between visitors and the art contained in the museum.

The Neue Nationalgalerie is going through its first refurbishment since its construction. Led by David Chipperfield, the renovation efforts aim to modernize and optimize some areas of the museum. It should reopen in 2018.

Berlin State Library - Hans Scharoun

As with the Philharmonie across the street, the Staatsbibliothek's architecture reflects its function. It is, therefore, a “calmer” building, characterized by an unassuming facade and its golden-cladded archive block. Also as the Philharmonie, it redefined its typology and became and model for modern library designs. It is a massive building, over 200 meters long. Its floorplan resembles a ship bow, which gave it the nicknames of “book ship,” “book steamer,” or “ocean giant.” The large archive box, cladded in gold and laying on top of the library stands out from afar. Up close, you can see the low entrance which leads to the foyer and then to the reading hall. The reading room is a terracing landscape in a tall and vast space, lit by skylights and north facing windows overlooking the Kulturforum. It is beautiful.