Pier Luigi Nervi and his buildings in Rome

Three beautiful buildings from the Italian master of concrete in Rome: the Paul IV Audience Hall, the Palazzo dello Sport and the Palazzetto dello Sport

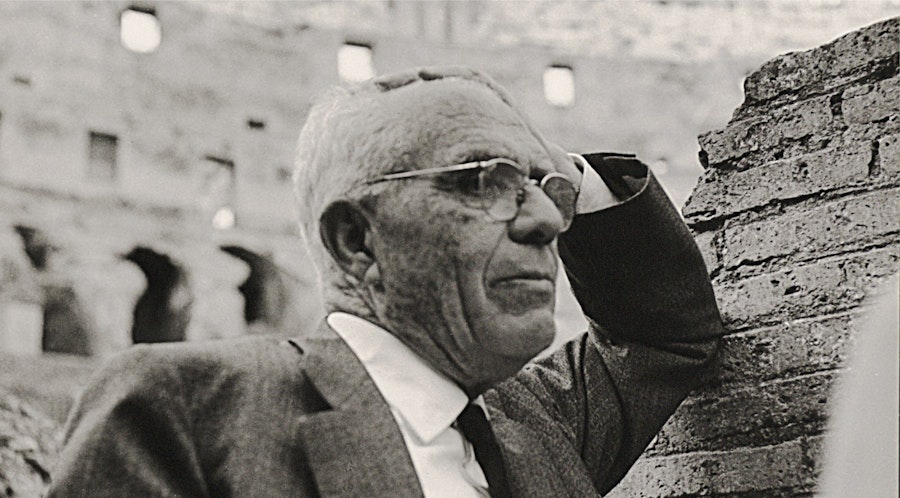

As part of the upcoming Rome Contemporary Architecture Guide, I inevitably had to learn more about the Italian engineer/architect Pier Luigi Nervi.

Called "the great Italian god of concrete in the 20th century," Nervi explored the potential of prefabrication and reinforced concrete to create beautiful buildings.

However, for Nervi, beauty was never the goal, but the simple result of the combination of technology, structure, functionality, and economy.

"Beauty does not come from decorative effects but from structural coherence. Formal beauty and technical perfection are inseparable."

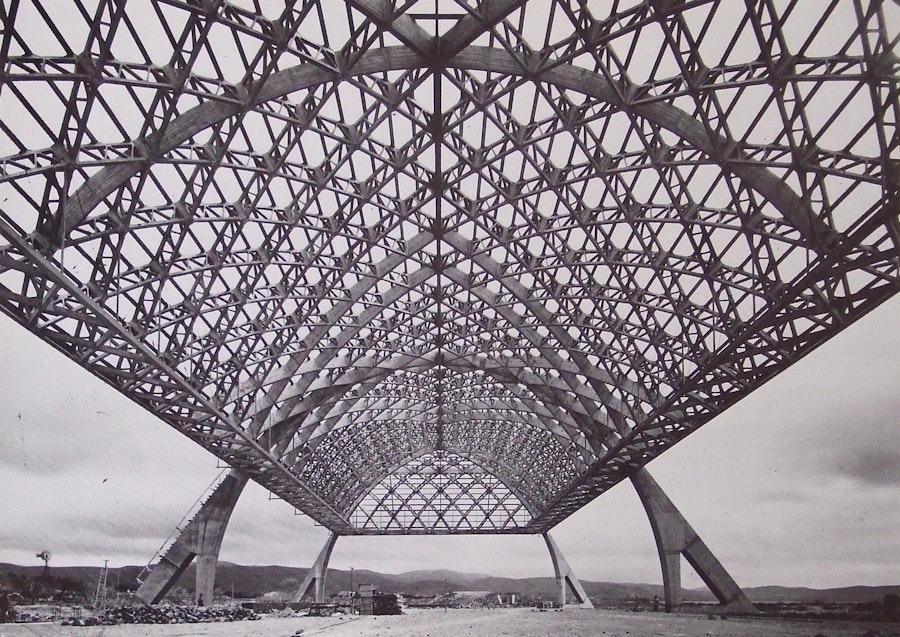

Nervi was born in 1891 and studied engineering at the University of Bologna. He started his career building airplane hangars for the Italian Army in the 1930s. These projects became a playground for experimentation in building techniques, and the results were a series of economic, fast-to-build, light, efficient buildings. They were, also, some of the most beautiful airplane hangars ever built.

The hangars were all inevitably destroyed during the war. To Nervi, however, they confirmed the potential of reinforced concrete as an exciting construction material.

"Adaptability to any form and the capacity to resist all three major stresses make reinforced concrete the most revolutionary material in the history of the construction industry […]The possibility to create cast stones of any form, which being more resistant to stress are better than the natural ones, is somewhat magic."

Nervi went on to dedicate his career to the innovative use of reinforced concrete. After the war, he further developed his research by helping rebuild many factories and carrying out proposals and studies which even included boat hulls made with the material. His mastery of concrete bespoke a love for its adaptability. "Concrete is a living creature which can adapt itself to any form, any need, any stress," he once said.

Despite experimentation and contribution to the technical development of engineering and construction, much of his genius came from how he approached the design process. Nervi believed that intuition should be used as much as mathematics in design, if not more.

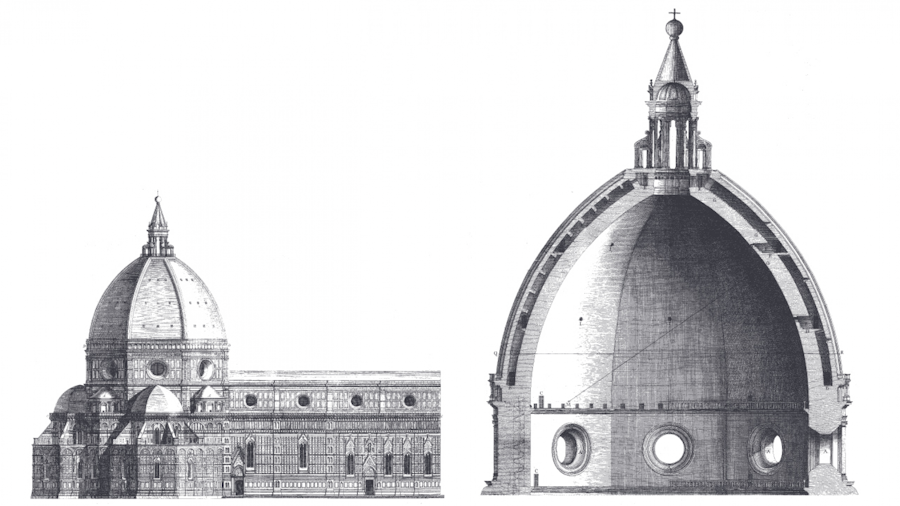

During his time as an engineering professor at the University of Rome, Nervi tried to persuade students that, when it comes to structural design, mathematics is not enough . In his classes, Nervi demonstrated how Greek and Roman builders, and even Renaissance architects, were able to build great and monumental architecture without having the mathematical and scientific tools modern engineers do. For Nervi, Brunelleschi's work, for example, represented one of the most prominent examples of the primacy of intuition and static sensibility over mere mathematics.

"The conception of a structural system is a creative action only partly based on scientific data; static sensitivity entering in this process, although deriving from equilibrium and strength considerations, remains, in the same way as aesthetic sensitivity, an essentially personal aptitude"

Nervi's buildings are a visual representation of all his ideas. And, in Rome, you can experience some of the most extraordinary examples of his approach.

Paul VI Audience Hall

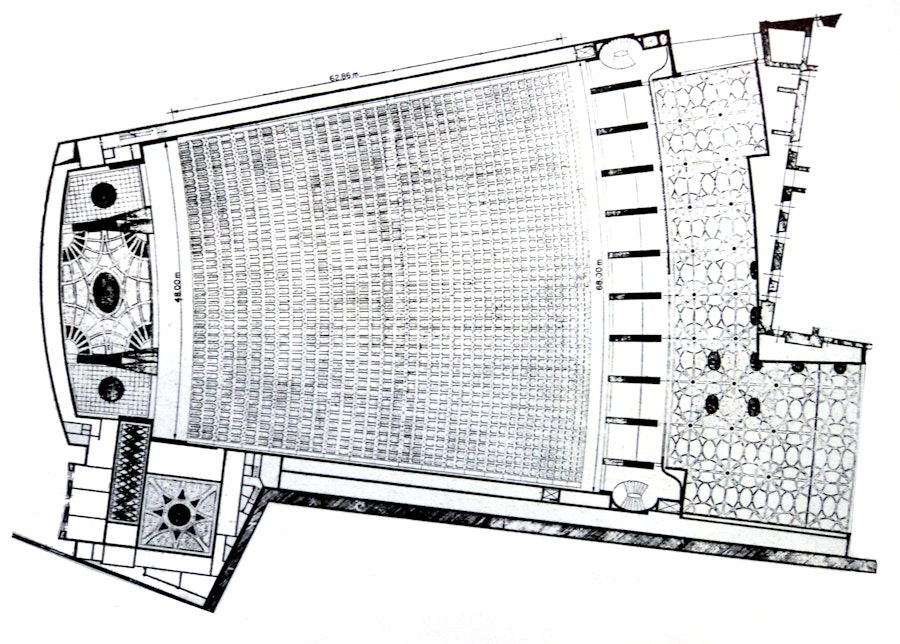

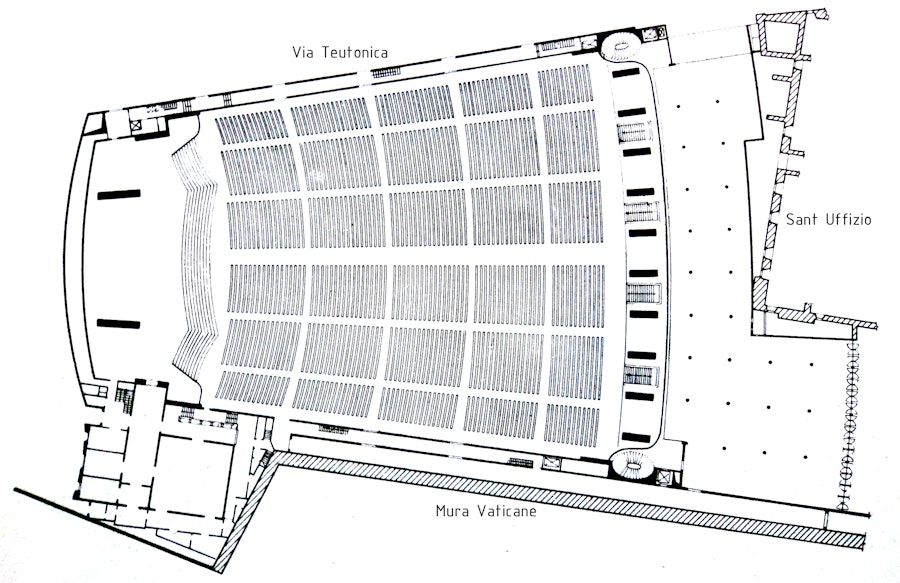

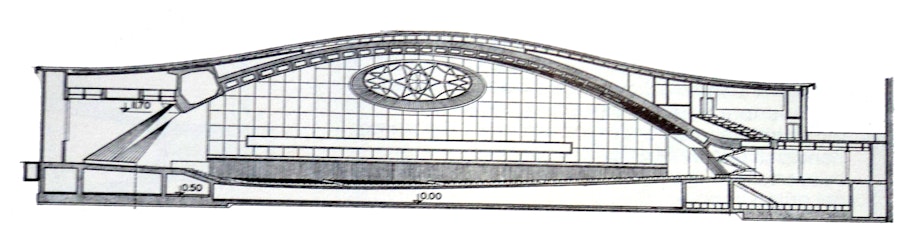

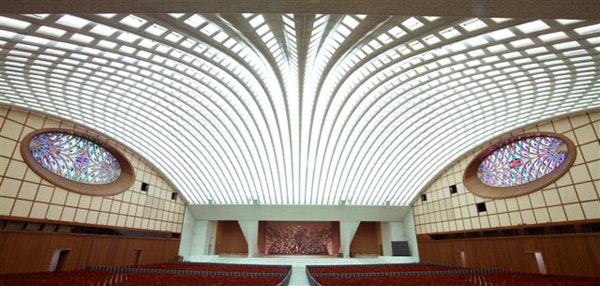

The Paul IV Audience Hall is one of the latest buildings in Nervi’s career, completed in 1971. It was designed entirely by Nervi after a commission by Pope Paul VI to improve the conditions in which the most crowded audiences were held.

Nervi designed a single room covered by a vault consisting of 41 elementary parabolic arches with a span of 70 meters, each composed of 18 prefabricated corrugated elements of variable height and length.

The roof vault has a dramatic effect of drawing the attention of the whole room to the stage, where the Pope delivers his addresses. The use of a unique mix of marble dust with the concrete gives the ribbed ceiling a bright appearance, reflecting light coming from skylights and two large oval windows into the hall.

Succeeding renovations led to the Vatican winning the 2008 Euro Solar Prize for turning its football field-sized roof into a giant solar-power generator. Also, theories emerged about the design, which pointed to its uncanny resemblance to a snakehead.

However, it is still a simple, effective, and beautiful structure.

Palazzo dello Sport

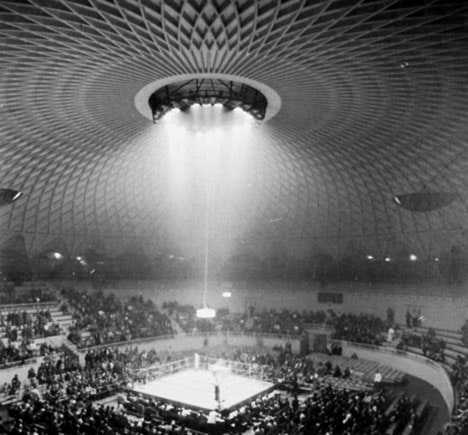

The Palazzo dello Sport is part of a series of buildings erected for Rome's Olympics in 1960.

It was designed by architect Marcello Piacentini in 1957 and had its reinforced concrete dome designed and built by Nervi. The arena hosted the basketball games during the Olympics.

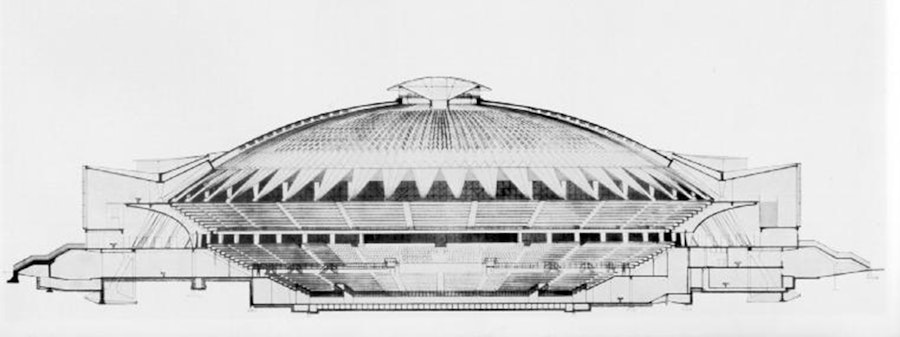

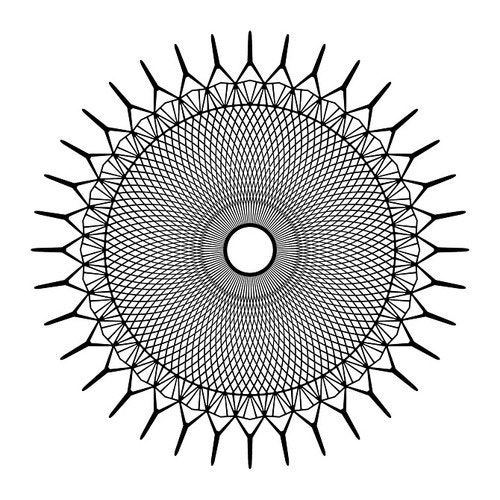

From the outside, it is a simple construction - a disc-like, glazed structure. Its interior, however, is magnificent: a 100-meter, column-free span covered by a domed roof which culminates in an oculus at its center. The roof structure is composed of thin lines radiating from the oculus, supported at the dome's edges by triangular elements. The sheer scale of the space and the symmetry of its radial structure is mesmerizing.

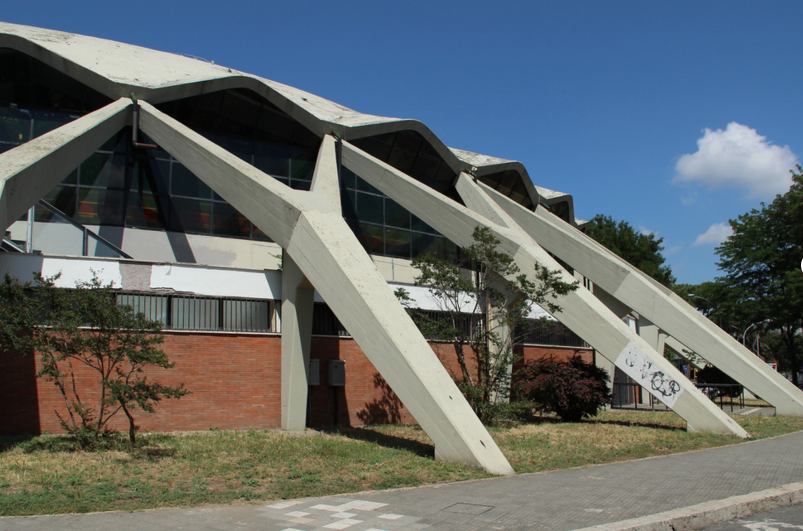

Palazzetto dello Sport

This is, however, the highlight of Nervi's buildings in Rome. Also, the one that left the most significant impression on me during my visit.

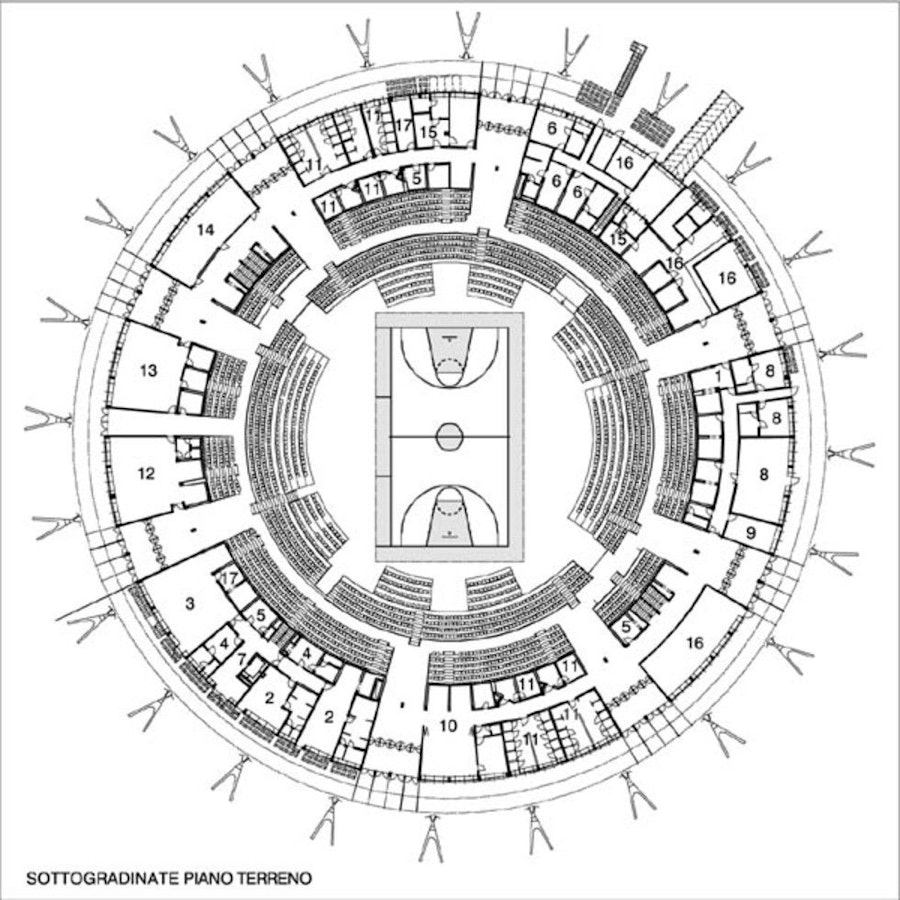

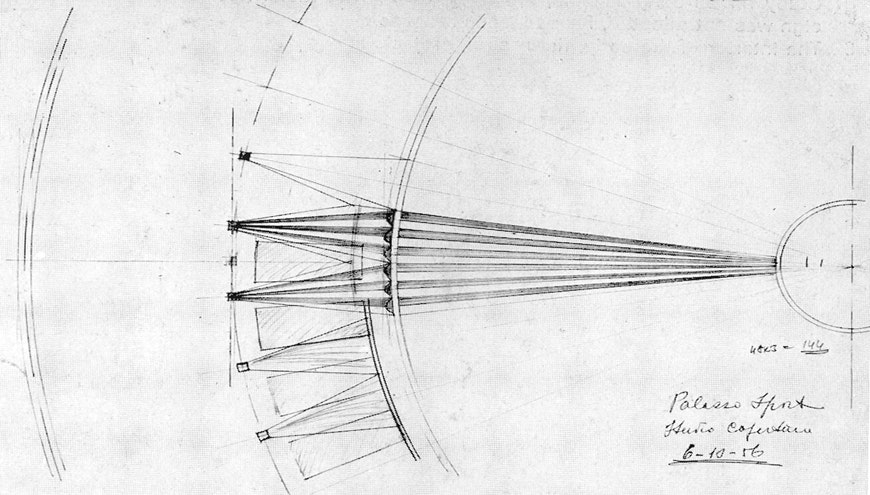

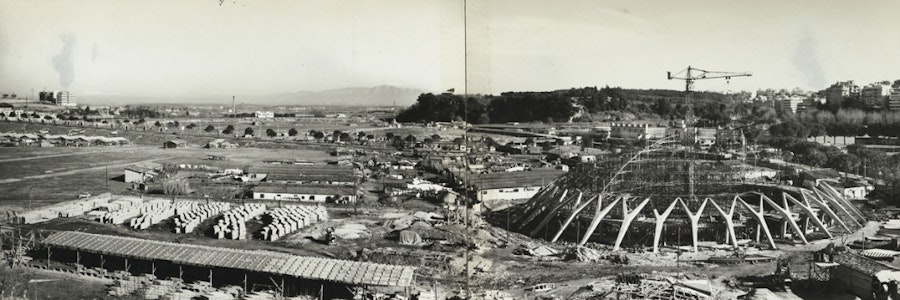

In 1954, the Italian National Olympic Committee (CONI) commissioned the design of a prototype medium-sized sports facility to be replicated in every Italian city. The building had to be very simple and cost-effective.

Together with architect Annibale Vitellozzi, Nervi proposed a project whose estimated cost was incredibly low: 200 million liras (around 2.5 million euro, today).

.jpg?fit=max&auto=format&w=900)

.jpg?fit=max&auto=format&w=900)

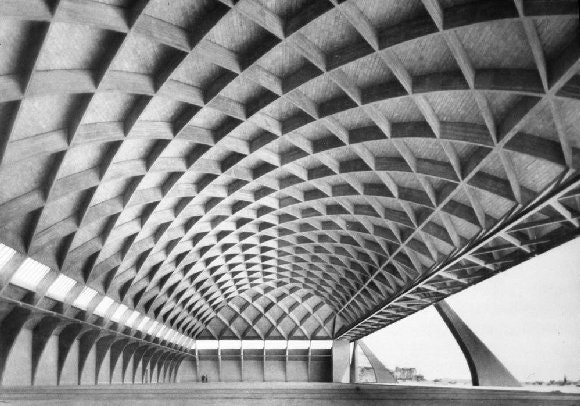

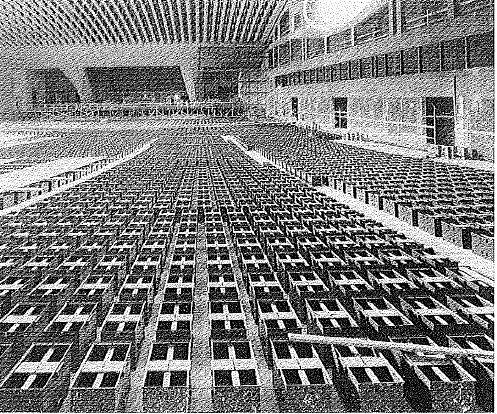

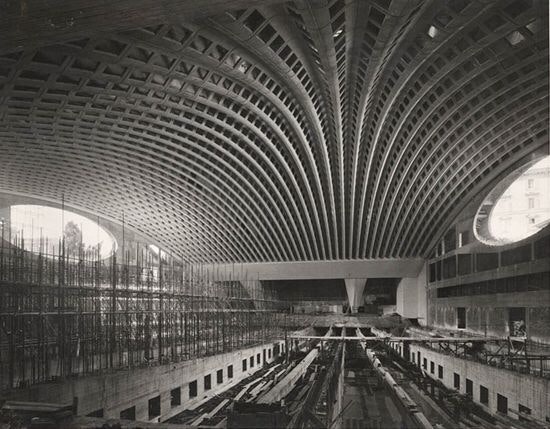

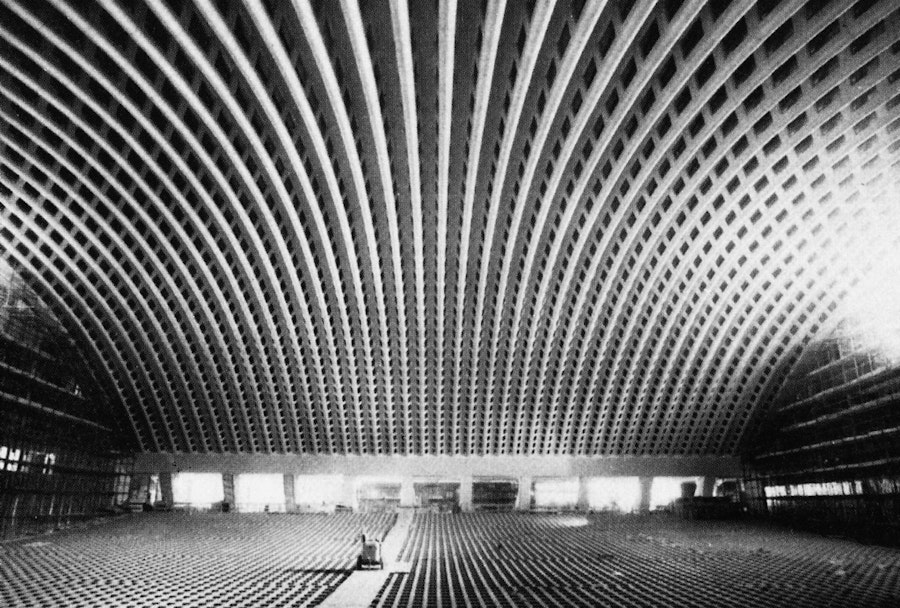

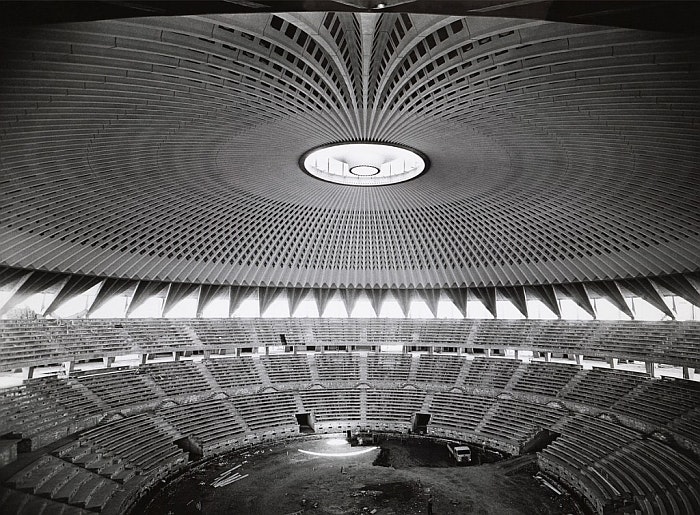

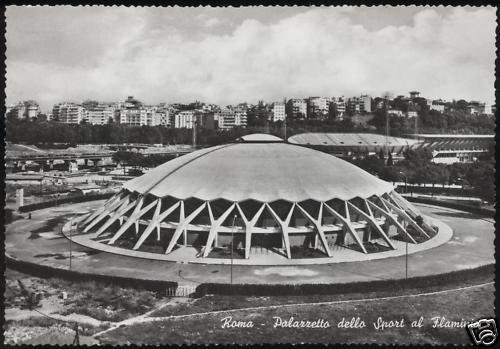

The final design was basic: a low-rising dome, with a 60-meter-wide circular plan. It was supported by 36 Y-shaped inclined trestles spaced, placed 10 degrees apart from each other.

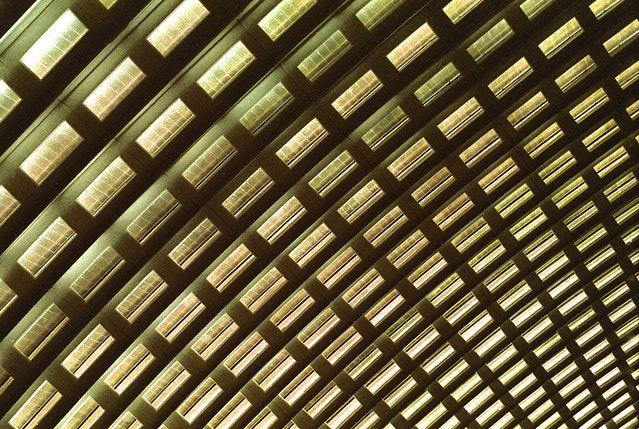

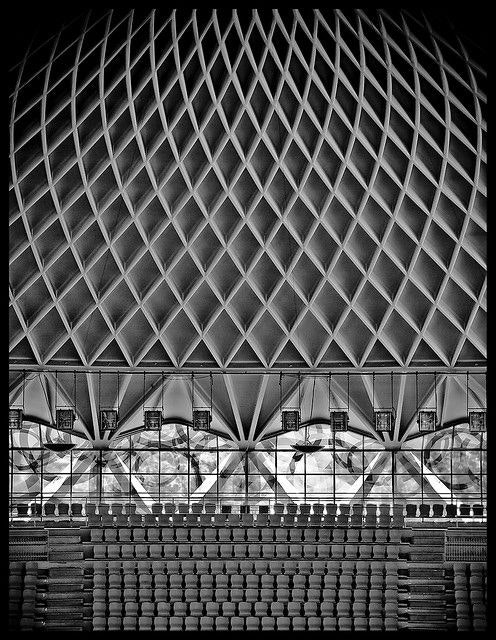

The dome was made up of 1,620 small, rhomboidal "tavelloni." In total, 13 different types of blocks that, once assembled in place, would create the dome as if it were a vast mosaic.

Each hollow block was small enough to be made by hand and moved by two workers. This way, the expensive wooden support typical of concrete constructions was no longer needed, which made the whole system extremely cost-effective.

The building was erected in 61 days. The result is a small sports arena placed under a concrete dome. The connection between these two elements is a series of continuous ribbon windows, uninterrupted. This transparency gives the impression that the roof is levitating. Together with the delicate weave of the dome's visible structure, it gives the whole space incredible lightness and beauty.

.jpg?fit=max&auto=format&w=900)

.jpg?fit=max&auto=format&w=900)

In his writings, Nervi always reminded readers that 90 percent of his contracts were awarded in competitions where the governing factors were economy and speed of construction. He thrived on these limitations and, indeed, "never found this relentless search for economy an obstacle to achieving the expressiveness of form" desired.

Architecture, for Nervi, was "a synthesis of technology and art." To find the logical solution to a limiting set of factors within a highly competitive situation was, for him, "to build correctly."

The buildings above are direct translations of these principles. A must-see for any architect visiting Rome. As much as Nervi tried to learn from the past, we also have much to learn from him.

This is part of the upcoming Rome Contemporary Architecture Guide. Stay in the loop for future updates by joining the TFA Mailing list:

Subscribe to my newsletter

I will send you a weekly email on Mondays. I promise it will always be interesting! And you can unsubscribe at any time.